Blog Archives

Egypt’s proposed electoral system

I’m about a week late to this but Egypt’s transitional military government has released a draft law of the country’s new electoral system. The draft is somewhat short on details, such as minimum thresholds, but the basic thrust is that 1/3 of seats would be allocated through closed-list PR and the rest would use the individual candidacy system that is currently in place. This means that each district has two candidates and each elector gets two votes. If no candidate receives an absolute majority in the first round, a second round is held one week later.

Photo property of David Jandura

A rough translation of this from the draft law:

The individual candidate shall be elected by the absolute majority of valid votes cast in the election. If the two candidates who gained the absolute majority were not workers and peasants, the one with the largest number of votes shall be declared elected, and a re-election in the constituency shall be conducted between the candidates from workers and peasants who obtained the largest number of votes. In this case, the one with the largest number of votes shall be declared elected.

If there was no absolute majority for one of the candidates in the constituency, a re-election shall be conducted among the four candidates who obtained the largest number of votes, provided at least half of them are workers and peasants. In this case, the two candidates who got the highest number of votes shall be declared elected.

I will have more to say on this, but my main point is the individual tier, as it exists, is highly candidate-centric and will greatly weaken political parties. In particular, the two-round, two-seat system creates an incentive for local elites to make grand bargains that further undermine an already weak party system. Two elites, for example, can make a bargain where they tell their supporters to cast their two votes for each of them – a de facto joint ticket. Those same elites could then make separate deals with weaker candidates. This would entail a promise to support the weaker candidate in the second round (should they make it) in exchange for first-round support for themselves.

The nascent party system in Egypt is very weak. A recent IRI poll shows that of all existing parties, Al Wafd garners the most support with a paltry six percent. Parties as institutions also suffer from worse approval ratings than state-owned media and the hated business community. Creating even a small PR tier is a welcome move but I certainly hope the final law will make it much larger than 1/3 of all seats.

The importance of individuals in open list PR

Hong Kong's Legislative Council Building. Photo property of Baycrest

The Hong Kong government recently announced a proposal to change the way they fill vacant seats in the Legislative Council. Hong Kong elects its MPs through open list proportional representation; the current method of filling a vacant seat is through a special election. While this seems somewhat intuitive, a special election is actually inconsistent with the values of a PR system. Awarding seats proportionally only really works if you have multiple seats up for grabs at once; otherwise, it just becomes a standard SMD race where the two largest parties will dominate. Most countries fill empty seats by picking the next in line candidate on the previous office holder’s party list. The new Hong Kong proposal, however, is to replace the vacant seat with the first unelected candidate on the party list that had highest number of remainder votes in the previous election. What does this mean? Proportional representation systems rely on quotas to evenly allocate seats to each party. This works by using as system where each seat in a legislature corresponds to a raw number of votes, equal to a quota. A party’s total seat total then, depends on the number of quotas it wins in an election. Although there are various ways to allocate seats (largest remainder or highest average method) no PR system can perfectly award seats in one-to-one relation to vote shares as leftover votes are bound to exist. Giving the seat to the first candidate on the list with the largest remainder then, is essentially giving it to the first candidate who did not win a seat in the last election.

A Government spokesman said, “A vacancy arising mid-term in the geographical constituencies (GCs) or the newly established District Council (second) functional constituency (DC (second) FC) seats will be filled by reference to the election result of the preceding general election. The first candidate who has not yet been elected in the list with the largest number of remainder votes in the preceding general election will be returned. These constituencies adopt the proportional representation list voting system. The proposed replacement mechanism is consistent with the proportional representation electoral system and reflects the overall will of the electors expressed through the general election.”

This is interesting because it assumes that individual candidates are driving vote choice more than party label. There are five constituencies in Hong Kong for thirty seats, so the average district magnitude any party list competes on is around five or six. I’m guessing this small district magnitude is what’s leading them to conclude that personalities matter. Hong Kong uses the Hare quota to allocate seats, the simplest method of seat allocation and one that generally favors smaller parties. As Hong Kong seems to return several small parties to parliament with one seat each, maybe they assume that the individual candidate who captured that seat was a big reason for the party’s success. To me this is contrary to what the literature would suggest. According to Carey and Shugart, low district magnitude in open list PR decreases the incentive for a candidate to cultivate a personal vote. In contrast, it is in high magnitude, open list PR where candidate preference matters more. This is because in a larger list, candidates have a stronger incentive to distinguish themselves from their fellow list members. Ultimately, we don’t really know why any individual is voting the way they are, but I think the Hong Kong government’s assumption requires more explanation.

Egypt reveals new electoral law, stalls on system design

Egypt’s military government announced amendments to the electoral law today, although noticeably absent was any mention of the country’s electoral system. From what I gather the debate is currently between list pr and single member districts although the details of either have been nonexistent.

While it’s nice they aren’t rushing such an important decision I do think they need hurry up if they want to hold the September elections on time. District creation takes time, at least if you want to do it fairly. Furthermore, this is creating an unfair burden on political parties who have no way of devising electoral strategies. If a nationwide, list pr system is adopted this is not nearly as big a deal, but that is unlikely. Any sort of district creation, however, will force parties to prioritize where they run candidates.

All electoral systems force tactical voting, but Egypt’s fractionlized party system will place an extraordinary burden on voters. In order to cast a tactical vote, a citizen must know the relative strength of each party. This allows an individual to avoid wasting a vote on a party that has no chance of winning, while picking the best option that has a realistic shot at victory. In Egypt, the electoral viability of any given party or candidate in a district will be largely unknown, and the longer it takes to draw district, the less time elites will have in providing that information to voters .

Formal models that predict the effective number of parties, optimal organization strategies for parties, and tactical voting decisions by electors, are all based on the assumption that actors have an understanding of the parties’ strength. I believe this lack of information will disproportionality hurt secular and liberal parties, while favoring the more organized Muslim Brotherhood. The reason for this? The Brotherhood occupies a space on the right of the political spectrum larger than any liberal party occupies on the left. Tactical voting, in other words, will be a much greater challenge for these voters. Or to use a Downsean model, the cost of obtaining information for a conservative is far less than that for liberals. It may be the case that Egypt’s military rulers are putting of the decision on an electoral system in an effort to make the election fair. The longer it takes for them to decide, however, the less legitimate the results will be.

Egypt to abandon current electoral system

It looks like Egypt will be scrapping its current electoral system in favor of some sort of mixed or parallel system. I’ll have more to say on this soon, but the short takeaway is this is terrific news for secular and liberal parties. Egypt’s current system creates several coordination problems and favors local elite powerbrokers over actual parties.

Vote choice and referendums

Apparently they didn't

Via Matthew Shugart comes this discussion at the LSE blog about public opinion and electoral system reform in the United Kingdom.

One of the takeaway points for me is that voters have consistently voiced strong support for systems that are more proportional, but that support quickly evaporates once it is described to them what a proportional representation system is. This isn’t that surprising; traditional tradeoffs between fair and effective governance, although overstated, are easier to make when they are abstract. When you start to think about how they will impact your preferred party, however, things might be different.

This made me curious to see if there has been anything written about vote choice and direct democracy, with a particular interest in the impact of elite signaling. The best thing I found was this paper by Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, which discuss how different variables about a referendum affect vote choice. Examining data from fourteen European integration referendums, Hug and Sciarini essentially claim that issue saliency determines voting behavior. In important “first-tier” elections, voters make a decision by weighing the actual issue. On less important “second-tier” elections, voters may base their decision on their assessment of the ruling party. This comes in the form of voting against the wishes of the government if one is dissatisfied, and voting in favor if one is supportive. This makes sense but it only explains voting behavior using a rational choice/retrospective model, where voters retroactively form their opinions of parties after evaluating their performance in office.

I’m not against looking at things this way, but I don’t think it’s appropriate for every type of referendum. The UK AV referendum, in particular, doesn’t fit any existing model. I’m not sure if the election would count as “first or second tier” in importance – the 40 percent turnout leads me to believe second – but I don’t think it matters. Even if it was first tier, voters would not be able to punish the ruling government as it was made up of a coalition divided on the issue. To me, it’s very difficult for a voter to not weigh the issue through a partisan filter because the referendum is essentially a vote on future partisan performance. Yet, as we’ve previously discussed here, there still seemed – at least according to one earlier survey – that a decent amount of partisans were going against their party. I would like to see more written about this by people who know more and have more data to play with. I’m guessing that committed Tory and LibDem partisans took cues from their party leaders. Labour partisans, having been sent such mixed signals from thier elites, would be interesting to examine. Did Labour voters have a clear idea over whether AV would help or hurt them? I think you could make arguments either way but I’m not sure what they heard. Also, how did those with weak identification vote, if they even turned out?

Britain overwhelmingly rejects election reform

With almost all constituencies counted it looks like the AV referendum will, as predicted, fail miserably. There were some hopes that suppressed turnout would allow AV to squeak out a victory but that was probably quite wishful thinking. The Guardian has a good article providing ten reasons AV failed. Not being the expert on British politics that I would like to be I can’t evaluate most of them critically, but they generally sound plausible.

The talk of weak turnout benefiting the “Yes” camp surprised me, because I would have thought that a referendum like this would require an absolute majority of registered voters to turnout in order to be valid. Extra stipulations like this are quite common in plebiscites worldwide and I think they are generally a better option. There is a lot of evidence that direct democracy, far from giving more power to the people, is just another channel for elites to push for their interests. California is the easiest example of this, as the state’s propositions have more special interest money spent on them than campaigns for elected office. Given how easy it is for a small group of intense policy demanders to get their way, I think requiring an absolute majority of voters to turnout is a good idea. This will ensure those groups can’t push through harmful changes based on the apathy of the general public (Yes I realize this still happens all the time in legislatures but we shouldn’t make it easier). The extra hurdle does matter; Moldova recently failed to alter its method for electing the president – despite 87 percent of voters approving the change – due to insufficient turnout. Like in the UK, voting reform was highly political in Moldova, and I think major changes to a country’s institutions should be based on broad legitimacy.

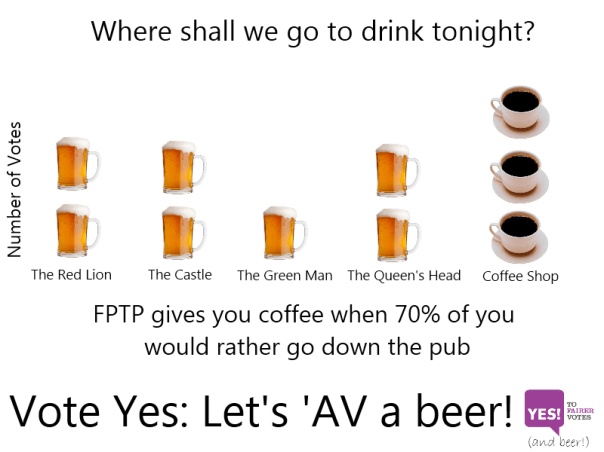

Let’s ‘AV a beer!

As I’ve previously mentioned, citizens of the UK will go to the polls tomorrow to decide whether to adopt an Alternative Vote (AV) system, or retain FPTP. As a non-Brit, I’m strongly in favor of voting reform. While I think the benefits of AV are overstated, FPTP is generally a horrible system that only manages to stay around because it institutionalizes itself through the party system it helps create. But don’t take my word for it, here is the best pitch for AV.

Canada’s new party system?

Canada held snap elections yesterday in which Steven Harper’s Conservative Party managed to secure a parliamentary majority. The New Democratic Party (NDP) essentially supplanted the Liberals as the left opposition in the country, while the center-left Liberals, who had dominated Canadian life for decades, saw their seat total plummet. Likewise, the separatist Bloq Quebecois were reduced to a small four seats.

Canada isn’t normally thought to be an interesting country (Something which they should take as a complement; interesting countries tend to have more problems!) but buried in the lackluster coverage are a few gems worth election wonks pondering over. The first is the fact that the final results were far different than initial polling would suggest. When snap elections were called in March, the Liberals were still the leading opposition party with the NDP solidly behind. This is pretty strong evidence that the campaign mattered. Not shocking to many, but certainly to those who are aware of the significant literature that suggests campaigns are really only important at the margins. Recall the recent British elections where the Liberal Democrats under Nick Clegg’s leadership surged in the polls, only to wind up right where they started when the results were tallied. The LibDem’s performance, of course, may be partially attributable to tactical voting, which brings me to my next point regarding Duverger’s Law.

In Les Partis Politique, Marice Duverger explained how plurality votes in single-member districts would bring the effective number of competitive candidates to two. ‘Duverger’s Law’ as it was dubbed by William Riker was taken by some to mean that (1) SMD systems would always produce only two viable parties, and (2) that there would only be two effective parties at the national level. These two misconceptions have led many to incorrectly state that Canada and India are proof Duverger’s law has been broken. The problem, I think, is that what Duverger was explaining wasn’t really a law so much as a force, and is in this respect completely true. Gary Cox in Making Votes Count does a good job of rescuing Duverger while expanding on his theory with his ever helpful equation, N+1, to predict an electoral system’s impact on the number of candidates. (N being the number of available seats in the district, the number of candidates would be one more). A quick glance at the results seem to indicate that Duverger’s Force was certainly in effect. I’m guessing once the NDP took the mantle of the leading non-conservative party, voters evaluated it as their best option in a single member district. It’s hard to say if Canada’s party system will stay like this after the next election, but I think there is a decent amount here for us to digest for now.

Alternative Voting campaigns in the UK

On May 5, UK citizens will head to the polls in a special referendum to decide if the country should move to an Alternative Voting (AV) system. Unfortunately, recent polling predicts the measure will fail as the “no” campaign seems to be building a bigger lead. There are plenty of places to read about the politics of the referendum, so I just wanted to focus on the campaign tactics being used by the respective camps and briefly speculate if there is any evidence they are having an impact on vote preference . First, there is this widely clever ad from the “Yes” campaign.

This is a great advertisement, but it’s actually not the main talking point of the “Yes” campaign, which seems to be pushing the notion that AV will make Representatives work harder.

Your next MP would have to aim to get more than 50% of the vote to be sure of winning. At present they can be handed power with just one vote in three. They’ll need to work harder to get – and keep – your support.

This doesn’t sound like the most convincing argument to me, although I’m sure it was the message that tested the best in focus groups. Still, I find it much better than this “No” campaign spot, which seems to better represent that campaign’s overall message.

In order to understand how an AV system works you need to be able to count to three; it’s really not much harder than that. This isn’t, however, a surprising line of attack; efforts at voting reform in the United States have often run up against the same. As misleading as that ad was, I think the false trade-off between critical national interests and voting is even more absurd.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Are any of these campaigns effective? I think the evidence from surveys show that it’s difficult to prove:

The poll shows that while Liberal Democrat voters are overwhelmingly in favour of reform (66 per cent to 26 per cent) and Conservative voters are overwhelmingly opposed (76 per cent to 19 per cent), Labour voters remain divided, with 47 per cent backing FPTP No and 41 per cent backing AV.

To me, this implies that vote choice might be predominantly a function of partisan preference; the Michigan Model for the United Kingdom. Of course I don’t really know enough about UK politics to know if partisan attachment is more or less stable than the United States. I would think the nature of their parties would make it more so, which would lead me to expect a greater correlation between party ID and preference on AV. Still the fact that support for the referendum has swung so drastically, with a large number of undecideds moving to one camp, may be evidence that people who have not paid much attention are now taking cues from party elites. Not the best way to choose an electoral system, but another example that they are highly endogenous to their political environment.