Author Archives: JD

Ethnic party formation in Estonia

The Estonian Centre Party (Eesti Keskerakond)

The OSCE/ODIHR has just released its assessment of February’s Riigikogu elections. The report devotes considerable discussion to Estonia’s internet voting system, which I’ve previously talked about. Also in the report is a discussion of the state of minority Russians in Estonia. Although technically twenty-six percent of the population, Russians are underrepresented in politial life. In fact, only ten percent of the previous parliaments’ MPs belonged to any minority at all. Furthermore, strict citizenship laws that requre Estonian lanaguage skills mean a large portion of Russians are not even allowed to vote.

Political parties made varying degrees of effort to include persons belonging to national minorities on their candidate lists and to reach out to Russian-speaking voters. One party that explicitly identified itself along ethnic lines did not meet the five per cent threshold. Estonia’s public broadcaster aired some election debates in Russian on TV and radio, while political parties and some individual candidates issued campaign materials in both Estonian and Russian. Issues related to national minorities did not feature prominently in the campaign.

Prior to the elections, the Estonian Cooperation Assembly/Roundtable of Nationalities, a network of civil society organizations, issued an appeal to election contestants and the public to take a more constructive approach to Estonia’s ethnic and linguistic diversity.

Estonia’s party system has been extremely unstable since its independence. Russians initially formed ethnic parties such as the Estonian United People’s Party and managed to gain some representation in parliament. In the last decade, however, ethnic Russian voters started to move their support to non-ethnic, mainstream parties such as the Centre Party and Reform Party. While the latter two haven’t made their platforms extremely Russian friendly – Reform favors stricter citizenship laws than exist now – they have both included significantly more ethnic Russians on their party lists. It’s interesting that mainstream elites have wanted, and been able, to recruit ethnic Russians into their parties. I’m guessing – although open to being corrected – that poor organization and performance of the ethnic parties allowed this to happen. It probably also doesn’t hurt that there are so many ethnic Russians in the country (lots of votes!). It’s my general observation that once ethnic parties become institutionalized, it’s rare for their voters to move to a different party. Estonia might provide a great research design for anybody looking at the impact of strong ethnic parties as the country now has a time series change regarding their salience.

Vote choice and referendums

Apparently they didn't

Via Matthew Shugart comes this discussion at the LSE blog about public opinion and electoral system reform in the United Kingdom.

One of the takeaway points for me is that voters have consistently voiced strong support for systems that are more proportional, but that support quickly evaporates once it is described to them what a proportional representation system is. This isn’t that surprising; traditional tradeoffs between fair and effective governance, although overstated, are easier to make when they are abstract. When you start to think about how they will impact your preferred party, however, things might be different.

This made me curious to see if there has been anything written about vote choice and direct democracy, with a particular interest in the impact of elite signaling. The best thing I found was this paper by Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, which discuss how different variables about a referendum affect vote choice. Examining data from fourteen European integration referendums, Hug and Sciarini essentially claim that issue saliency determines voting behavior. In important “first-tier” elections, voters make a decision by weighing the actual issue. On less important “second-tier” elections, voters may base their decision on their assessment of the ruling party. This comes in the form of voting against the wishes of the government if one is dissatisfied, and voting in favor if one is supportive. This makes sense but it only explains voting behavior using a rational choice/retrospective model, where voters retroactively form their opinions of parties after evaluating their performance in office.

I’m not against looking at things this way, but I don’t think it’s appropriate for every type of referendum. The UK AV referendum, in particular, doesn’t fit any existing model. I’m not sure if the election would count as “first or second tier” in importance – the 40 percent turnout leads me to believe second – but I don’t think it matters. Even if it was first tier, voters would not be able to punish the ruling government as it was made up of a coalition divided on the issue. To me, it’s very difficult for a voter to not weigh the issue through a partisan filter because the referendum is essentially a vote on future partisan performance. Yet, as we’ve previously discussed here, there still seemed – at least according to one earlier survey – that a decent amount of partisans were going against their party. I would like to see more written about this by people who know more and have more data to play with. I’m guessing that committed Tory and LibDem partisans took cues from their party leaders. Labour partisans, having been sent such mixed signals from thier elites, would be interesting to examine. Did Labour voters have a clear idea over whether AV would help or hurt them? I think you could make arguments either way but I’m not sure what they heard. Also, how did those with weak identification vote, if they even turned out?

Britain overwhelmingly rejects election reform

With almost all constituencies counted it looks like the AV referendum will, as predicted, fail miserably. There were some hopes that suppressed turnout would allow AV to squeak out a victory but that was probably quite wishful thinking. The Guardian has a good article providing ten reasons AV failed. Not being the expert on British politics that I would like to be I can’t evaluate most of them critically, but they generally sound plausible.

The talk of weak turnout benefiting the “Yes” camp surprised me, because I would have thought that a referendum like this would require an absolute majority of registered voters to turnout in order to be valid. Extra stipulations like this are quite common in plebiscites worldwide and I think they are generally a better option. There is a lot of evidence that direct democracy, far from giving more power to the people, is just another channel for elites to push for their interests. California is the easiest example of this, as the state’s propositions have more special interest money spent on them than campaigns for elected office. Given how easy it is for a small group of intense policy demanders to get their way, I think requiring an absolute majority of voters to turnout is a good idea. This will ensure those groups can’t push through harmful changes based on the apathy of the general public (Yes I realize this still happens all the time in legislatures but we shouldn’t make it easier). The extra hurdle does matter; Moldova recently failed to alter its method for electing the president – despite 87 percent of voters approving the change – due to insufficient turnout. Like in the UK, voting reform was highly political in Moldova, and I think major changes to a country’s institutions should be based on broad legitimacy.

Let’s ‘AV a beer!

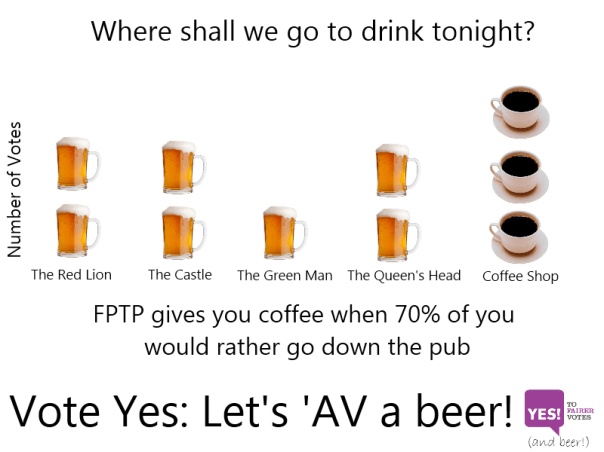

As I’ve previously mentioned, citizens of the UK will go to the polls tomorrow to decide whether to adopt an Alternative Vote (AV) system, or retain FPTP. As a non-Brit, I’m strongly in favor of voting reform. While I think the benefits of AV are overstated, FPTP is generally a horrible system that only manages to stay around because it institutionalizes itself through the party system it helps create. But don’t take my word for it, here is the best pitch for AV.

Canada’s new party system?

Canada held snap elections yesterday in which Steven Harper’s Conservative Party managed to secure a parliamentary majority. The New Democratic Party (NDP) essentially supplanted the Liberals as the left opposition in the country, while the center-left Liberals, who had dominated Canadian life for decades, saw their seat total plummet. Likewise, the separatist Bloq Quebecois were reduced to a small four seats.

Canada isn’t normally thought to be an interesting country (Something which they should take as a complement; interesting countries tend to have more problems!) but buried in the lackluster coverage are a few gems worth election wonks pondering over. The first is the fact that the final results were far different than initial polling would suggest. When snap elections were called in March, the Liberals were still the leading opposition party with the NDP solidly behind. This is pretty strong evidence that the campaign mattered. Not shocking to many, but certainly to those who are aware of the significant literature that suggests campaigns are really only important at the margins. Recall the recent British elections where the Liberal Democrats under Nick Clegg’s leadership surged in the polls, only to wind up right where they started when the results were tallied. The LibDem’s performance, of course, may be partially attributable to tactical voting, which brings me to my next point regarding Duverger’s Law.

In Les Partis Politique, Marice Duverger explained how plurality votes in single-member districts would bring the effective number of competitive candidates to two. ‘Duverger’s Law’ as it was dubbed by William Riker was taken by some to mean that (1) SMD systems would always produce only two viable parties, and (2) that there would only be two effective parties at the national level. These two misconceptions have led many to incorrectly state that Canada and India are proof Duverger’s law has been broken. The problem, I think, is that what Duverger was explaining wasn’t really a law so much as a force, and is in this respect completely true. Gary Cox in Making Votes Count does a good job of rescuing Duverger while expanding on his theory with his ever helpful equation, N+1, to predict an electoral system’s impact on the number of candidates. (N being the number of available seats in the district, the number of candidates would be one more). A quick glance at the results seem to indicate that Duverger’s Force was certainly in effect. I’m guessing once the NDP took the mantle of the leading non-conservative party, voters evaluated it as their best option in a single member district. It’s hard to say if Canada’s party system will stay like this after the next election, but I think there is a decent amount here for us to digest for now.

The Virtues of Political Parties

I’m reading Nancy L. Rosenblum’s defense of political parties in her book, On the Side of the Angels. I already had a strong appreciation for parties, so it’s always nice to hear their virtues clearly articulated. While Rosenblum seems to be primarily writing to other political theorists, her message really needs to be told to citizens of struggling Central European countries, whose original expectations of democratic elections were unrealistic, or citizens in Sub-Saharan African counties like Zambia, Mozambique, or South Africa, where one party rule creates false accountability. I would guess, however, that nobody in those countries would have the attention span to make it through Rosemblum’s book, which while good, is much longer than I felt it needed to be. (She also has a tendency to litter scare quotes and quotations so often, it is nearly impossible to distinguish if she is quoting a fellow academic, or merely suggesting her own words are misleading.)

Some of Rosenblum’s themes, however, are important, and I wish she had shortened her book to focus on them. In particularly, her chapters where she writes about civil society and banning certain political parties have relevance for many transitioning and weak democracies. The tendency to view civil society as a substitute for parties, for example, is a common problem among democracy promoters working with less than democratic parliaments. Similarly, the debate over what should be a legal political party is timely given the events in the Middle East. I found Rosenblum dealt with these issues very well, offering a fair summary of the tradeoffs for banning parties based on different criteria. I tend to agree with her that any justification for banning a party runs into serious problems. The rule that a party can’t challenge the fundamental system of a government, for example, may sound like a good argument in the United States, but King Mohammed VI of Morroco could easily make the same statement while justifying the ban of a party that started demanding more power be invested in parliament.

The notion that there is a way to distinguish an acceptable party platform in a country assumes that there is a consensus on the fundamental structure of state institutions. Yet if there is a true consensus, then a party attempting to challenge it should garner few votes and pose little threat. Excluding them could only serve to push them out of the political arena and onto the streets. If the party does build substantial support, however, then there is clearly not a consensus on the legitimacy of the state. This does not mean that electoral engineering can never be a legitimate tool for state and nation building, but that it might not always be the best, or adequate, solution. In post-independence or post-conflict societies, political parties – some with violent pasts – may have to work together to build an uneasy consensus on the nature of the state. Here especially it is difficult to ban a party based on a platform.

Alternative Voting campaigns in the UK

On May 5, UK citizens will head to the polls in a special referendum to decide if the country should move to an Alternative Voting (AV) system. Unfortunately, recent polling predicts the measure will fail as the “no” campaign seems to be building a bigger lead. There are plenty of places to read about the politics of the referendum, so I just wanted to focus on the campaign tactics being used by the respective camps and briefly speculate if there is any evidence they are having an impact on vote preference . First, there is this widely clever ad from the “Yes” campaign.

This is a great advertisement, but it’s actually not the main talking point of the “Yes” campaign, which seems to be pushing the notion that AV will make Representatives work harder.

Your next MP would have to aim to get more than 50% of the vote to be sure of winning. At present they can be handed power with just one vote in three. They’ll need to work harder to get – and keep – your support.

This doesn’t sound like the most convincing argument to me, although I’m sure it was the message that tested the best in focus groups. Still, I find it much better than this “No” campaign spot, which seems to better represent that campaign’s overall message.

In order to understand how an AV system works you need to be able to count to three; it’s really not much harder than that. This isn’t, however, a surprising line of attack; efforts at voting reform in the United States have often run up against the same. As misleading as that ad was, I think the false trade-off between critical national interests and voting is even more absurd.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Are any of these campaigns effective? I think the evidence from surveys show that it’s difficult to prove:

The poll shows that while Liberal Democrat voters are overwhelmingly in favour of reform (66 per cent to 26 per cent) and Conservative voters are overwhelmingly opposed (76 per cent to 19 per cent), Labour voters remain divided, with 47 per cent backing FPTP No and 41 per cent backing AV.

To me, this implies that vote choice might be predominantly a function of partisan preference; the Michigan Model for the United Kingdom. Of course I don’t really know enough about UK politics to know if partisan attachment is more or less stable than the United States. I would think the nature of their parties would make it more so, which would lead me to expect a greater correlation between party ID and preference on AV. Still the fact that support for the referendum has swung so drastically, with a large number of undecideds moving to one camp, may be evidence that people who have not paid much attention are now taking cues from party elites. Not the best way to choose an electoral system, but another example that they are highly endogenous to their political environment.

A formal model of talking animals crossing rivers

Via James Fallows, come this great metaphor, about a frog and scorpion, for Earth Day:

“There is a serious question about whether we should worry more about slow-heating crises like carbon pollution (poached frogs) or seemingly improbable catastrophes like the Japanese tsunami and nuclear failure (black swans). The answer may lie in another zoologically suspect fable, the frog that is persuaded to ferry a scorpion across a river. The frog believes it is safe because it would not be in the scorpion’s self interest to sting it midstream. The scorpion does so anyway, saying “It’s my nature.” Current conservative theory assures us that we can trust markets to avoid oil gushers in the ocean, nuclear meltdowns on our coastlines, and climate catastrophe for our children. But we’ll still get stung, because when corporations see a profit, they just can’t help themselves.”

The part of me that hates junk science loves this story as, while obviously fiction, isn’t the debunked boiling frog metaphor that people still use so often. The part of me that loves political science, however, hates it because it’s a failure of rational choice theory in favor of a cultural argument.

The Icesave Referendum

On April 9, Icelanders will head to the polls for a special referendum regarding a loan guarantee to Britain and the Netherlands. This is the second time Iceland will vote on the issue; last year, voters overwhelmingly rejected a similar ballot initiative.

In October 2008, the Icelandic bank, Landsbanki, collapsed, and with it its online Icesave branch, and the investments of 400,000 British and Dutch savors. Iceland’s Depositors’ and Investors’ Guarantee Fund lacked the funds to compensate its investors and the Icelandic government initially refused to take responsibility for the failure of a private bank. After consdierable negotiations, Iceland agreed to insure the liabilities of Icesave, while the British and Dutch governments provided a 3.8 billion Euro loan to cover the deposit insurance obligations for their citizens. In August 2009, the Icelandic parliament, the Althing, passed a bill setting out terms of repayment to the two countries for the loan. President Olafur Grimsson, however, refused to sign the bill, forcing a nationwide referendum on the issue. In March 2011, Icelandic voters overwhelmingly voted against the measure, with 93 percent casting “no” votes. The rejection resulted in severe diplomatic tension between Iceland and both Britain and the Netherlands. It also caused a downgrading of Iceland’s bond ratings.

On February 16, 2011, the Althing passed a new Icesave bill, with terms considered more favorable for Iceland. The new terms were the result of negotiations with the British and Dutch, and included lower interest rates on repayment as well as a revaluing of the debt. Once again, however, President Grimsson refused to sign the bill, meaning voters will once again be given the chance to weigh in on the issue. While initial support for the referendum started out strong, recent polls have shown the gap narrowing. A survey taken on March 17 revealed that a bare majority, 52 percent, were planning on voting “yes”, while 48 percent planned to once again reject the proposal. The most recent poll, taken on April 5-6, shows that 55 percent of respondents planned on rejecting the referendum, while 45 percent would approve it.

It’s easy to criticize Icelanders (and indeed I am right now!) for not insuring their own banks, but I understand where they are coming from. Think of the uproar over our bank bailout several years ago. Now imagine if we were being asked to bail out AIG so we could pay back the bad investments of a bunch of British and Dutch! Different scenario yes, but the politics are similar. Furthermore, unlike our bailout, Iceland basically knows how much this will cost the average citizen. Given the relative small size of the country, coupled with the high price tag for the loan, the average Icelander is expected to shell out – not all at once of course – around 6,000 dollars. Of course saying “no” will downgrade Iceland’s debt to junk bond status, and cripple EU membership talks. It’s a bad situation to be in and the average Icelander is not to blame. Rich bankers in their country over-expanded, bad investors in other countries weren’t careful with their investments. Now they have to share the loss.