Cote d’Ivoire is capturing headlines for all the wrong reasons, but there is another African nation that finds itself in a tense post-election environment. Ikililou Dhoinine on Sunday won the second round of presidential elections in the Comoros islands. Dhoinine captured 61 percent of the vote while his main competitor, Mohamed Said Fazul, took 33 […]

Category Archives: Electoral Systems

Britain overwhelmingly rejects election reform

With almost all constituencies counted it looks like the AV referendum will, as predicted, fail miserably. There were some hopes that suppressed turnout would allow AV to squeak out a victory but that was probably quite wishful thinking. The Guardian has a good article providing ten reasons AV failed. Not being the expert on British politics that I would like to be I can’t evaluate most of them critically, but they generally sound plausible.

The talk of weak turnout benefiting the “Yes” camp surprised me, because I would have thought that a referendum like this would require an absolute majority of registered voters to turnout in order to be valid. Extra stipulations like this are quite common in plebiscites worldwide and I think they are generally a better option. There is a lot of evidence that direct democracy, far from giving more power to the people, is just another channel for elites to push for their interests. California is the easiest example of this, as the state’s propositions have more special interest money spent on them than campaigns for elected office. Given how easy it is for a small group of intense policy demanders to get their way, I think requiring an absolute majority of voters to turnout is a good idea. This will ensure those groups can’t push through harmful changes based on the apathy of the general public (Yes I realize this still happens all the time in legislatures but we shouldn’t make it easier). The extra hurdle does matter; Moldova recently failed to alter its method for electing the president – despite 87 percent of voters approving the change – due to insufficient turnout. Like in the UK, voting reform was highly political in Moldova, and I think major changes to a country’s institutions should be based on broad legitimacy.

Let’s ‘AV a beer!

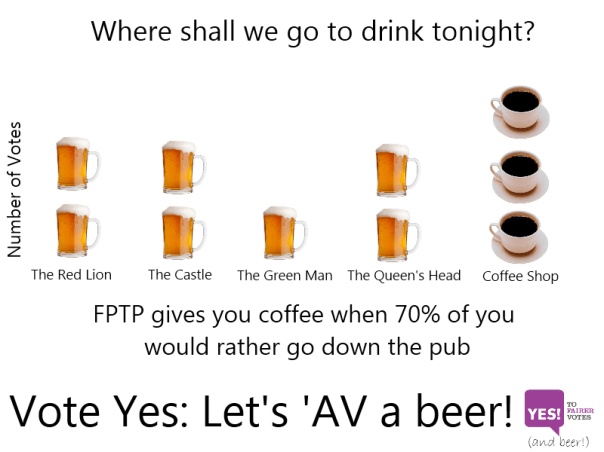

As I’ve previously mentioned, citizens of the UK will go to the polls tomorrow to decide whether to adopt an Alternative Vote (AV) system, or retain FPTP. As a non-Brit, I’m strongly in favor of voting reform. While I think the benefits of AV are overstated, FPTP is generally a horrible system that only manages to stay around because it institutionalizes itself through the party system it helps create. But don’t take my word for it, here is the best pitch for AV.

Canada’s new party system?

Canada held snap elections yesterday in which Steven Harper’s Conservative Party managed to secure a parliamentary majority. The New Democratic Party (NDP) essentially supplanted the Liberals as the left opposition in the country, while the center-left Liberals, who had dominated Canadian life for decades, saw their seat total plummet. Likewise, the separatist Bloq Quebecois were reduced to a small four seats.

Canada isn’t normally thought to be an interesting country (Something which they should take as a complement; interesting countries tend to have more problems!) but buried in the lackluster coverage are a few gems worth election wonks pondering over. The first is the fact that the final results were far different than initial polling would suggest. When snap elections were called in March, the Liberals were still the leading opposition party with the NDP solidly behind. This is pretty strong evidence that the campaign mattered. Not shocking to many, but certainly to those who are aware of the significant literature that suggests campaigns are really only important at the margins. Recall the recent British elections where the Liberal Democrats under Nick Clegg’s leadership surged in the polls, only to wind up right where they started when the results were tallied. The LibDem’s performance, of course, may be partially attributable to tactical voting, which brings me to my next point regarding Duverger’s Law.

In Les Partis Politique, Marice Duverger explained how plurality votes in single-member districts would bring the effective number of competitive candidates to two. ‘Duverger’s Law’ as it was dubbed by William Riker was taken by some to mean that (1) SMD systems would always produce only two viable parties, and (2) that there would only be two effective parties at the national level. These two misconceptions have led many to incorrectly state that Canada and India are proof Duverger’s law has been broken. The problem, I think, is that what Duverger was explaining wasn’t really a law so much as a force, and is in this respect completely true. Gary Cox in Making Votes Count does a good job of rescuing Duverger while expanding on his theory with his ever helpful equation, N+1, to predict an electoral system’s impact on the number of candidates. (N being the number of available seats in the district, the number of candidates would be one more). A quick glance at the results seem to indicate that Duverger’s Force was certainly in effect. I’m guessing once the NDP took the mantle of the leading non-conservative party, voters evaluated it as their best option in a single member district. It’s hard to say if Canada’s party system will stay like this after the next election, but I think there is a decent amount here for us to digest for now.

Alternative Voting campaigns in the UK

On May 5, UK citizens will head to the polls in a special referendum to decide if the country should move to an Alternative Voting (AV) system. Unfortunately, recent polling predicts the measure will fail as the “no” campaign seems to be building a bigger lead. There are plenty of places to read about the politics of the referendum, so I just wanted to focus on the campaign tactics being used by the respective camps and briefly speculate if there is any evidence they are having an impact on vote preference . First, there is this widely clever ad from the “Yes” campaign.

This is a great advertisement, but it’s actually not the main talking point of the “Yes” campaign, which seems to be pushing the notion that AV will make Representatives work harder.

Your next MP would have to aim to get more than 50% of the vote to be sure of winning. At present they can be handed power with just one vote in three. They’ll need to work harder to get – and keep – your support.

This doesn’t sound like the most convincing argument to me, although I’m sure it was the message that tested the best in focus groups. Still, I find it much better than this “No” campaign spot, which seems to better represent that campaign’s overall message.

In order to understand how an AV system works you need to be able to count to three; it’s really not much harder than that. This isn’t, however, a surprising line of attack; efforts at voting reform in the United States have often run up against the same. As misleading as that ad was, I think the false trade-off between critical national interests and voting is even more absurd.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Keeping a FPTP system will help the UK fund its military in the same way cutting NPR will help the United States eliminate the national debt. This ad is even more insulting than the last.

Are any of these campaigns effective? I think the evidence from surveys show that it’s difficult to prove:

The poll shows that while Liberal Democrat voters are overwhelmingly in favour of reform (66 per cent to 26 per cent) and Conservative voters are overwhelmingly opposed (76 per cent to 19 per cent), Labour voters remain divided, with 47 per cent backing FPTP No and 41 per cent backing AV.

To me, this implies that vote choice might be predominantly a function of partisan preference; the Michigan Model for the United Kingdom. Of course I don’t really know enough about UK politics to know if partisan attachment is more or less stable than the United States. I would think the nature of their parties would make it more so, which would lead me to expect a greater correlation between party ID and preference on AV. Still the fact that support for the referendum has swung so drastically, with a large number of undecideds moving to one camp, may be evidence that people who have not paid much attention are now taking cues from party elites. Not the best way to choose an electoral system, but another example that they are highly endogenous to their political environment.

What reality TV can teach us about election managment

Not a lot it turns out, but enough for a blog post.

The structure of an Electoral Management Body (EMB) is a critical element in effective and fair election administration. The legal framework for how the members of an EMB are appointed varies greatly from country to country, with each model offering a unique set of advantages and disadvantages.

Although practitioners should be aware that local context is important, it is always helpful to have an understanding of how EMB design can shape incentives and affect the management of elections. In a paper submitted to APSA, Barry C. Burden, David T. Canon, Stéphane Lavertu, Kenneth R. Mayer, and Donald P. Moynihan have explored the effect of partisan EMB membership on the body’s behavior. In their paper, Election Officials: How Selection Methods Shape Their Policy Preferences and Affect Voter Turnout, the authors find that how clerks are selected has a noticeable impact on the body’s priorities.

We employ a uniquely rich dataset that includes the survey responses of over 1,200 Wisconsin election officials, structured interviews with dozens of these officials, and data from the 2008 presidential election. Drawing upon a natural experiment in how clerks are selected, we find that elected officials support policies that emphasize voter access rather than ballot security, and that their municipalities are associated with higher voter turnout. For appointed officials, we find that voter turnout in a municipality is noticeably lower when the local election official’s partisanship differs from the partisanship of the electorate. Overall, our results support the notion that selection methods, and the incentives that flow from those methods, matter a great deal. Elected officials are more likely to express attitudes and generate outcomes that reflect their direct exposure to voters, in contrast to the more insulated position of appointed officials.

I think the recent kerfuffle with Bristol Palin does a good job of demonstrating this tradeoff in priorities. Bristol Palin, daughter of the ubiquitous Sarah, lost in the Dancing with the Stars finale the other night. Palin’s run generated a fair amount of controversy due to the fact that she kept advancing despite receiving poor scores from the judges. This was exacerbated after accusations surfaced of Tea Party activists exploiting a glitch in ABC’s internet voting system that allowed supporters to cast an infinite amount of votes. Whether of not this electronic ballot stuffing actually happened in a way that influenced outcomes, it demonstrates how incentives shape behavior for EMBs. ABC’s incentive for the show’s voting system was access, not security, which is a perfectly understandable tradeoff for what they were doing. There were definitely steps ABC could have taken to strengthen the verification process, but it would have probably reduced convenience for users. We shouldn’t be surprised that many reality TV systems have security holes, as long as there is a tradeoff with accessibility involved.

Related, electoral system design is also critical in reality TV voting. I noticed that Last Comic Standing, for example, used a Cumulative voting system. Viewers were allowed to cast ten votes, but could distribute those votes in anyway they wanted (meaning they could vote 10 times for one contestant). I’m guessing this method was employed in order to ensure adequate minority/female representation in the higher rounds. If we assume that female viewers are more likely to support female contestants, and the same being for minorities, than those viewers would be able to contribute all their votes to the few female candidates while men would spread their votes among men.

Our long national nightmare is over

Nov 5

I’m referring of course to Nauru, if that wasn’t obvious. Nauru is a pretty interesting country. In fact, unlike America, it actually is exceptional in a number of ways. For one it’s the only country to use a Borda count system for electing its parliament. (Slovenia uses a Borda count for two reserved seats for […]

Joementum can save Washington

Thomas Friedman has a new column out, which advocates the need for a third party in America to fix our broken system. This argument gets thrown out there quite frequently, but I was a bit surprised that I had to hear it from Friedman, who managed to write one of the most clueless articles I’ve read in a long time. It starts out with a comparison to the fall of Rome, which I’m sure in some way can teach us about the inevitable fall of the United States. I’m not sure how it is supposed to do this, but smart people have long told me that it is the case, so I suppose it’s true.

Friedman then moves on to his main argument; the American system is broken and it it going to cause a third party candidate to emerge.

But in talks here and elsewhere I continue to be astounded by the level of disgust with Washington, D.C., and our two-party system — so much so that I am ready to hazard a prediction: Barring a transformation of the Democratic and Republican Parties, there is going to be a serious third party candidate in 2012, with a serious political movement behind him or her — one definitely big enough to impact the election’s outcome.

Ah yes a third party will save America, just like Unity 08 did! I agree that it is bold to make a prediction that people make every cycle and almost never comes true. It’s also bold to make one that seems to ignore some entry level political science about why such an scenario won’t happen. But what is really annoying is the lack of an explanation over how a third party candidate could be effective at solving the problems that Friedman mentions. But maybe I’m speaking to soon, lets see if he manages to make a convincing case that a third party is needed to help our deadlocked system. Unfortunately, he doesn’t start out to well:

President Obama has not been a do-nothing failure. He has some real accomplishments. He passed a health care expansion, a financial regulation expansion, stabilized the economy, started a national education reform initiative and has conducted a smart and tough war on Al Qaeda.

Okay, starting out with a paragraph that basically disproves your entire argument that Washington isn’t working probably is not the best way to go, but I’ll keep reading.

There is a revolution brewing in the country, and it is not just on the right wing but in the radical center.

How did I know we were going to get here? I don’t know why Friedman wants us to feel bad for the poor ignored centrists who always lack a voice. But I’m even more curious as to why Friedman thinks the center can help us get out of this mess. For example, he goes on to list the things he laments were not accomplished, mainly a powerful climate bill, improved infrastructure, tougher financial regulation and a better health care bill. But does he really believe that a centrist third party would have made these things possible? Out of every problem he cites, I can’t think of one that wasn’t slowed down and weakened by the centrists in Congress. But no, I must be wrong, a clean energy bill surly would have been possible if only we had more Ben Nelsons in the Senate!

Friedman continues:

We need a third party on the stage of the next presidential debate to look Americans in the eye and say: “These two parties are lying to you.

I’m wondering at this point if Friedman wrote this article in about five minutes without doing a spot check on his logic. He talks about the need for a third party candidate to run for president, but every example he gives of special interests and good legislation getting stalled happens in….the Congress! In fact he acknowledges that the presidency isn’t the problem earlier in his piece:

Obama probably did the best he could do, and that’s the point. The best our current two parties can produce today — in the wake of the worst existential crisis in our economy and environment in a century — is suboptimal, even when one party had a huge majority.

So if we have a President with the right ideas, but is unable to pass his agenda because of the way congress operates, the obvious solution is to change the presidency, got it? I was happy to see Friedman quote Larry Diamond in the piece, but adding a second mustache doesn’t save this astonishingly clueless column.

Direct Democracy and Thresholds

Sep 27

On Saturday, Slovakia will vote on a six-question referendum, the seventh such vote in country history. In order for the referendum to be valid, more than half of all registered voters must turn out to the poll; a threshold most experts believe this vote will not meet. In fact, only one referendum in the country’s […]